By Ibanga Isine

In Parts I and II of this series, GuardPost revealed the impressive efficiency of security agents stationed at over 175 checkpoints, who managed to extract a modest N253, 596 from a 10-seater bus on the notorious international highway connecting Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and Ghana. Truly, a masterclass in law enforcement “service.”

Now, in this third part, we take a deep dive into our reporter’s tormenting (and money-sapping) encounters during the dangerous journeys. We hope this report prompts Nigeria, Benin Republic, Togo, and Ghana to finally round up their checkpoint cowboys and maybe—just maybe—give the dusty ECOWAS Treaty on free movement of people and goods the attention it deserves.

Passing through the Camel’s Eye

It is easier for a camel to squeeze through the eye of a needle than for West African nationals to travel by road across the sub-region. Our correspondent went undercover on six trips from Ghana to Nigeria and six more back to Ghana.

To fully understand the severity of the problem, we will in the coming parts examine the experiences of our correspondent more closely. Hopefully, it will serve as a wake-up call for authorities to act before these injustices become the accepted norm.

Nigeria’s Cocktail of Interlocking Checkpoints along Badagry-Seme Border

The Badagry-Seme border, a crucial gateway linking Nigeria to Benin Republic and the broader West African sub-region, has long become notorious for the staggering number of security checkpoints lining the route.

As shown in our previous reports, the 132 checkpoints operated by 10 agencies of the Nigerian government have created a punishing experience for travelers. While the intended goal might have been for enhanced national security and to combat smuggling, the proliferation of the roadblocks has led to excessive delays, harassment, and the extortion of road users, especially commercial drivers and passengers. Let us look at the operations of the agencies of the Nigerian government on the route.

Nigerian Security and Civil Defence Corps

Amid the relentless demands of almost every security agency along West Africa’s notorious “extortion corridor,” one agency stood out. Across six return trips made by our correspondent through these border crossings, where drivers faced near-constant demands for payments on entering or leaving the country, only one agency declined to partake in the practice.

It was the Nigerian Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC). Their refusal to collect bribes, even as other agencies lined up with outstretched hands, was not only surprising but also notable.

Whether this integrity extends to travelers on the local route between Lagos and Seme remains unconfirmed. For travelers going out of Nigeria, the NSCDC provided a rare glimpse of ethical conduct along the way and we can vouch for them.

Along the notorious Badagry-Seme corridor, the NSCDC maintained a total of four checkpoints—two positioned on the inbound lane and two on the outbound side of the dual carriageway.

Despite the presence of these checkpoints, none of the vehicles boarded by our correspondent were subjected to extortion or harassment by NSCDC officers. This was clearly a far departure from other security agencies encountered during the investigation.

This adherence to proper conduct by the NSCDC was very significant, given the widespread cases where we found operatives of other security agencies engaging in illegal activities along the route.

Nigerian Police

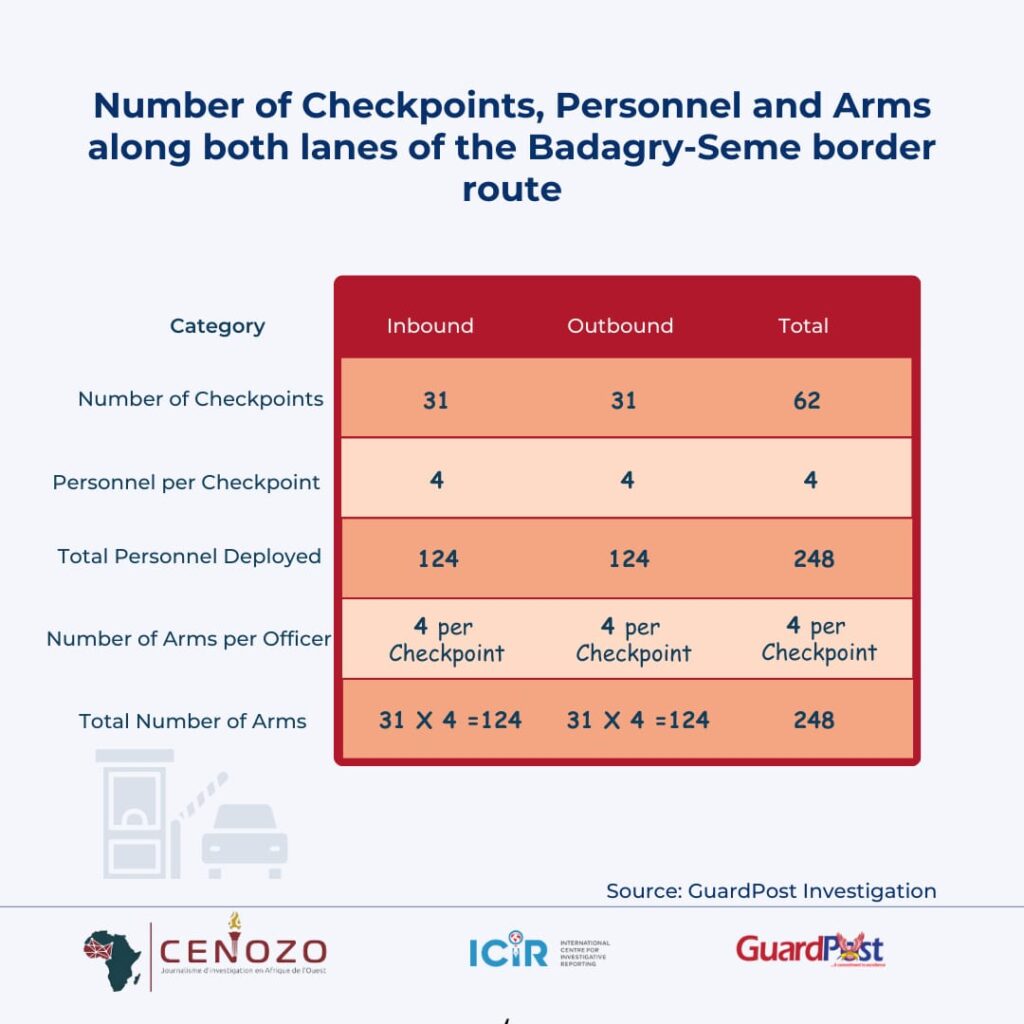

Despite having little statutory responsibility for border patrols, the Nigerian Police have managed to set up a jaw-dropping 62 checkpoints along the 18-kilometer stretch from Badagry to the Seme border —31 for incoming traffic and another 31 for those headed out. Quite the achievement for a force that is not even supposed to be there!

Commercial buses leaving the country or coming in faced fewer disruptions but the constant confrontations between police and local bus and taxi drivers at each checkpoint resulted in nerve-racking delays.

It is, however, important to note that the checkpoint count did not include any within the inner city of Lagos itself. We began the tally from Badagry.

Is it not very interesting that a country grappling with pervasive insecurity and an outrageously low police-to-citizen ratio would deploy such number of personnel and arms to an 18 kilometre stretch of road?

Little wonder when many drivers claim that a majority of the officers pay huge sums to secure postings to the border. Some are even said to go as far as getting loans with Shylock-level interests to make it happen.

A former Nigerian Deputy Inspector General of Police (IGP), who cannot be named, said an average police division has 80 personnel while the bigger ones in places like Lagos, Anambra and Rivers states and Abuja may have up to 200 and above.

When informed about the checkpoints and personnel we encountered along the Badagry-Seme Highway, he blamed the situation on poor coordination between the Force Secretary and the Operations Department in assigning the personnel.

“In a country facing severe security challenges, it’s entirely wrong to have that many checkpoints on a single stretch of road,” he began.

“This reflects a breakdown in communication between the Force Secretary’s office and the Department of Operations at the Force Headquarters. They’re not aligning on where officers are actually needed.

“There’s simply no reason to concentrate so many officers on one road while vast areas remain poorly policed,” the former DIG argued.

This was reechoed by Nigeria’s Inspector-General of Police (IGP) Olukayode Egbetokun on August 31, when he said insufficient manpower was hindering the efforts to tackle crime, saying that additional 190,000 personnel were needed to effectively police the country.

While the United Nations (UN) recommends one police personnel to 460- citizen ratio, he said Nigeria has a police-citizen ratio of 1:650. “The NPF requires an additional 190,000 personnel to be at parity with the United Nations recommended ratio,” said Mr. Egbetokun.

Could it be true the IGP is not aware of the deployment to Badagry/Seme Highway?

Despite the many police checkpoints along the Badary-Seme route, commercial bus drivers going to Ghana pay relatively low amounts in extortion to the police. Out of the 12 trips embarked by our correspondent, it was only once that a driver paid N1, 000 to a police officer in one of the checkpoints but they were actively extorting buses and taxis operating the local route.

Attempts to contact the Force Public Relations Officer, Olumuyiwa Adejobi, and the Lagos State Police Public Relations Officer (PPRO), Benjamin Hundeyin, regarding our findings were unsuccessful, as both officials did not answer phone calls or respond to text messages sent to their verified phone numbers.

You can also read – Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS)

The Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS) reigns supreme in extortion along the Badagry-Seme corridor, with an impressive 28 checkpoints. The most infamous of these is in Gbaji, where officers routinely halt vehicles and detain travelers for reasons that can only be described as absurd.

During several trips, our correspondent witnessed the NIS’s extortionary talents in action. While there were many contenders for “most outrageous incident,” one particular episode took the prize for sheer audacity.

Our correspondent was on a Lagos-to-Accra journey with a well-known transport company, and the bus had barely left the terminal when the driver’s phone rang. It was his colleague, the driver of the first bus, sounding like a man in a battle zone. Our correspondent was on the front seat of the vehicle with the driver.

The embattled driver, who had left an hour earlier, reported that two of his passengers had been detained by immigration officials at Gbaji. When the bus finally rolled up to the scene, our correspondent saw the two women sitting in the NIS’s shade by the roadside.

An operative named Victor, standing about 5.7 feet tall with a chocolate complexion, called out a name. A woman on the bus with our correspondent responded, and without missing a beat, Victor ordered her off the bus to join the two ladies already detained.

Unknown to passengers, the NIS operatives had already decided that the two earlier detainees were being trafficked to Ghana. Both women, who were over 25, tried to explain that they were traveling with a relative, who happened to be on the same bus as our correspondent, to work at her restaurant in Accra.

In an effort to prove her legitimate business, the lady who had been yanked off the bus by Victor presented both her resident and business permits, issued by the Ghanaian authorities. She explained that she owned a thriving restaurant in Accra and had brought the two ladies along to help cook special Nigerian dishes that were in high demand.

But the NIS operatives weren’t biting. Despite her papers and elaborate explanations, they insisted she was trafficking the women for prostitution. Unfazed, the two bus drivers refused to leave their passengers at the mercy of the unyielding officers and instead began negotiating for their release.

After nearly two hours of back-and-forth, N30, 000 was handed over to the operatives, and the women were finally freed. Of course, no receipt was issued, because who needs paperwork where extortion has become an art?

Our correspondent recorded a minimum of N14, 000 shaken down, and running over into corrupt pockets during each trip he embarked on.

The operatives were simply perfect in the art of highway robbery, one checkpoint at a time, without any side of bureaucracy to keep things official. After all in West Africa, a road trip is dull and uninteresting without a little extortion and harassment to spice things up.

When reached for comment, Enoch Aparshe, spokesperson for the Seme Border Command of the NIS, gave us the classic “not us!” response, assuring that his command has never been involved in shady deals.

He did, however, point out that the NIS only operates a “modest” five checkpoints—just three stationary and two mobile ones, all approved by the government.

Because, you know, nothing speaks to efficient border control like a cocktail of checkpoints stretched from Mile 2 to the Seme Border, run by the NIS, whose sole job is to stop irregular migration (and apparently not hold up traffic or extort motorists).

“You can verify from the reports of the Inter-Ministerial committee set up to checkmate the multiplicity of checkpoints along the corridor,” Mr. Aparshe said.

Nigerian Customs Service (NCS)

The Nigerian Customs Service (NCS) had the third-highest presence along West Africa’s notorious extortion corridor, with 24 checkpoints.

The service, which had a clean record during my 2019 investigation only extorted from the vehicles our reporter boarded at two checkpoints in Gbaji while entering and or leaving the country.

At the remaining checkpoints, the operatives generally waved drivers through, unless the vehicles were carrying large quantities of goods, in which case they were stopped for inspection and likely extortion.

In the course of our investigation, we found that drivers plying the Lagos- Accra route constantly drop (pay) a minimum of N2, 000 at the two NCS checkpoints in Gbaji.

Husaini Abdullahi, spokesperson for the NCS Seme Border Command, explained that his agency operates only two approved checkpoints and patrol bases.

“There’s a difference between a checkpoint and a patrol base. Patrol bases are set up in areas where we suspect smuggling activity, and we strategically deploy officers there. They aren’t checkpoints,” he said.

Insert picture: Smugglers moving unidentified goods in the night towards Nigerian border with Benin in Seme (Photo Credit- Ibanga Isine)

Trying hard to dismiss our findings, he added, “I don’t think we have the number of checkpoints you mentioned. We have a specific function we’re performing along that corridor.”

However, Mr. Abdullahi did promise to follow up: “I will cross-check with the relevant authority in our office to confirm the exact number, but I really don’t think it matches what you’re saying.”

When informed that NCS operatives at Gbaji were extorting drivers, Abdullahi responded, “We have three layers of operations in Gbaji—the Federal Operations Unit, the Border Drill, and the Command. I don’t think our officers are collecting money from drivers. That’s not even within our jurisdiction. Why would Customs collect money from drivers? What for?”

After being told our correspondent witnessed the extortion during six trips into Nigeria and six out, he softened his stance: “I’m not arguing with you. We will investigate this. I’ll discuss the matter with my controller, and we’ll take action. By God’s grace, I will get back to you with our findings.”

Nigerian Army (NA)

The Nigerian Army was not left out of the checkpoint party along the infamous route. They set up a cocktail of three checkpoints on each side of the dual carriageway between Badagry and Seme – and they were committed to their work! But when it came to extortion, their approach was more of “gentle persuasion” than full-blown aggression.

At one of the three checkpoints on either side of the highway, the soldiers worked with NCS operatives in a joint operation against diehard smugglers.

Our correspondent found that long-distance drivers had an unwritten rule: they simply had to drop off a “donation” at the soldier-manned checkpoints. Like submissive congregants at a very unconventional church service, offerings were casually surrendered in exchange for a polite wave to continue their journey.

Who would have believed that a road trip would come with such a charming blend of military decorum and extortion? In their very peaceful and friendly approach, the Army only collected a paltry N2, 000 from all the vehicles our correspondent boarded.

We tried reaching Major General Onyema Nwachukwu, the Army’s Director of Public Relations, through his verified mobile number and WhatsApp, hoping to discuss the little offering his soldiers were getting from motorists along the Badagry-Seme Highway.

But it seems the Major General had his phone on “do not disturb,” and neither picked up calls nor responded to our WhatsApp messages.

The Department of State Services (DSS)

The Department of State Services (DSS) set up two checkpoints, one on each side of the dual carriageway. While the Nigerian secret police managed to keep things calm and drama-free with drivers, they never missed out on receiving seeds, which radical Pastor Abel Damina has strongly kicked against.

But like the soldiers, the DSS had a laid-back approach and drivers just instinctively knew the drill and gave “willingly.” During our many trips, drivers usually forked over not more than N2, 000 at the DSS checkpoints.

A bus driver inserting money in a manifest sheet to give to a DSS official along Badagry-Seme Highway (Photo Credit- Ibanga Isine)

Due to the DSS’s new policy of opaqueness, as stated by its new Director General Oluwatosin Ajayi, it was not possible to obtain a response from the agency.

Former spokesperson Peter Afunanya, in a press briefing on September 4, announced that the service would be returning to a more secretive approach, especially in its dealings with the public and the media, particularly concerning information sharing.

National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA)

The National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) had six checkpoints along the route with three on each side of the dual carriageway. Unlike the DSS, their mode of operations presented a different story. They behaved like the overzealous bouncers, especially when young men and women sporting dreadlocks and “unique” fashion choices were onboard.

When these “suspicious” passengers were spotted, the NDLEA did not just conduct quick checks; they would turn the bus into a scene from a reality TV show, complete with thorough searches.

And when nothing incriminating was found, the drivers would still hand over their N1, 000 each at the two checkpoints. You can call it a tip for a performance that never really happened.

You would recall that it was the action of a notorious narcotic officer, who arrested and detained a young Ghanaian businessman for not traveling with a luggage that triggered this investigation.

NDLEA spokesperson, Femi Babafemi’s response to our findings was a perfect mix of courteous disbelief and “please, show me the evidence.”

“I wish you could share some evidence with us,” he said, probably thinking of seeing an exposé with an undercover reporter and secret recordings. “So we can identify and establish that the persons are our officers. That would put me in the right position to process what you have said.”

When informed that we are not allowed to share such details due to restrictions from our partners, Babafemi did not miss a beat. “Ah, well, you see,” he continued with the wisdom of someone who has seen a few things, “The whole essence of an investigation is to point out some social vices with a view to getting the appropriate authorities to correct them.”

He was not quite ready to bite on our claims without something more tangible. “I won’t be reacting to anything speculative,” he said, adding with a philosophical shrug, “just because you’re telling me doesn’t mean it’s true or false.”

Interestingly, Mr. Babafemi in 2023 admitted the NDLEA had set up a task force to investigate its staff after similar findings of extortion.

In a report published by HumAngle, anti-narcotic operatives, alongside other law enforcement agencies (let’s just say it was a team effort), were caught with their hands in the motorists’ cookie jar in Borno, North-east Nigeria. But yes, that was last year—different time, different location and allegations, right?

Federal Road Safety Commission (FRSC)

The Federal Road Safety Commission (FRSC), which had emerged squeaky clean in my 2019 undercover investigation, failed with flying colours on the Badagry-Seme corridor. Many drivers complained about a particular young officer, who seemed so determined to extort money from them at all cost.

“During one of our trips, we had the luck of meeting this overzealous road marshal in person, and, unsurprisingly, he did not disappoint. His routine? Stop vehicles, give them a quick search, and if they pass his impromptu “inspection,” collect quick cash with a smile. ”

If they failed, he would quickly refer them to his superiors for a more “thorough” review. Clearly, he had perfected the art of turning safety into a money-making venture. However, when he noticed our correspondent recording him, he refused the money the driver had discreetly wrapped in the manifest.

FRSC spokesperson, Olusegun Ogungbemide, said no FRSC staff has justification for extorting motorists, adding that those who do were risking their jobs.

“There is no ‘return syndrome’ in the FRSC,” Ogungbemide explained. “Our officers don’t collect bribes on behalf of anyone. We have a monitoring system both at the zonal and headquarters levels to check for any misconduct by our operatives on the highway.”

He added, “If anyone is caught with money and found guilty after due trial, they face dismissal. We have records of this over the years. Our officers are paid their salaries on time, so they can’t claim financial hardship as an excuse for taking bribes. The headquarters also ensures that monthly allocations are provided to the various commands.”

Mr. Ogungbemide concluded, “Any officer you see compromising on the highway is doing so at their own risk, fully aware of the consequences of their actions.”

Nigerian Port Health Services

For anyone thinking that only law enforcement officers have a knack for shaking down motorists, we want to clear up that misconception: officials of the Nigerian Port Health Services have mastered the same shameful art.

This agency, under the Federal Ministry of Health, is meant to provide prompt and effective services in line with global best practices for the reduction of morbidity, mortality, and disability due to communicable and non-communicable diseases at Nigeria’s points of entry and exit..

While the job description sounds noble, it turns out they are doing a bit more than checking for diseases. They are also skilled at checking motorists’ wallets, whether they are entering or leaving the country.

With two checkpoints on the outbound and two on the inbound lanes, these health “experts” collected a cool N4, 000 from every bus driver passing through. Apparently, contagious diseases are not the only things that need to be monitored, cash flow is also fair game.

Task Force

There are two checkpoints on each side of the dual carriageway, staffed by men and women that the drivers casually refer to as the “task force.”

However, during the course of our investigation, our correspondent observed that these task force members did not engage in any form of extortion.

Instead of the usual heavy-handed tactics, the officers were polite and professional. They maintained a calm and courteous conduct and always waved at drivers to continue their journey without delay or harassment.

It was almost refreshing to witness a checkpoint where the focus seemed to be on keeping traffic moving smoothly rather than extracting bribes. In a system afflicted by corruption and highhandedness, their behavior stood out as a rare display of integrity.

Bribe at the Last Post

At the border, every driver submitted their vehicle manifest and large sums of cash to the clearing agents, who would then share the money among the various security agencies operating there. It was not possible to determine the exact sharing formula, but each driver we spoke to confirmed they pay to clear both themselves and their vehicles before being permitted to cross. On the Nigerian side of the Seme border, drivers were handing over N30, 000 to agents during each trip.

This report was partly supported by the Norbert Zongo Cell for Investigative Journalism in West Africa (CENOZO) and Journalism Retool House, the charity arm of GuardPost Nigeria.