There’s a quiet revolution unfolding in the heart of Benin City; not on the marble floors of government offices, but on the gritty, weather-worn walkways of Oba Market. It’s not written in flowery speeches or painted on PR billboards, but told in the sun-darkened eyes and calloused hands of the traders who have lived through neglect, and are now witnessing governance reborn.

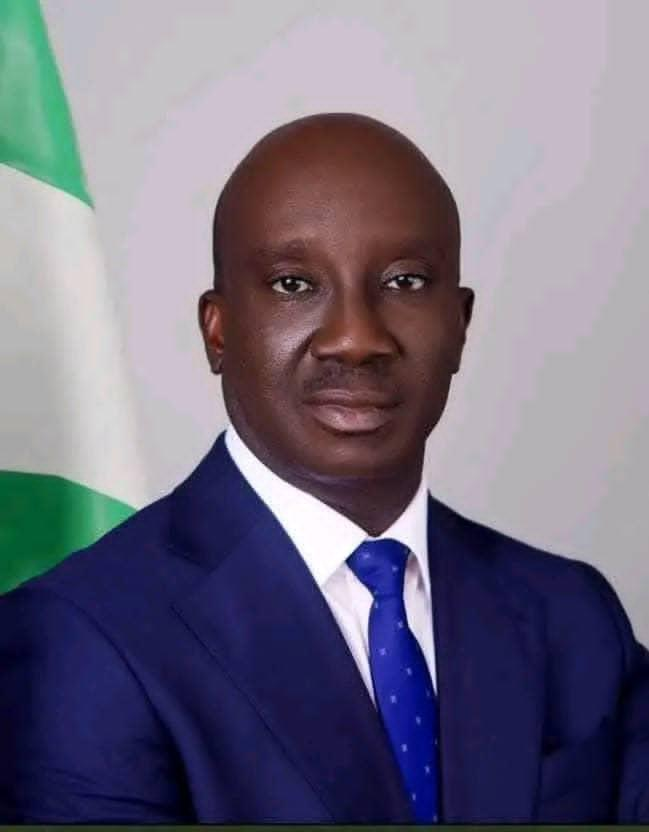

Once a sprawling sprawl of chaos, where commerce battled filth and fear daily, Oba Market is now humming with new energy: clean drains, regulated security, restored dignity. And in every corner, from the coral bead seller to the spice hawker, there is a single name on everyone’s lips: “Monday Okpebholo”.

They are not cheering for another promise. They are not clapping for a campaign trail handshake. They are bearing witness to a rare political phenomenon, a governor who shows up without sirens and fixes things without press conferences.

Take Blessing Eboigbe, for instance. A weathered foodstuff trader with decades behind her stall. “Every rainfall used to be a nightmare,” she says, recalling the way floodwater swallowed her livelihood. But since Okpebholo arrived, “They’ve dredged the drains, fixed the paths, and restored peace. I now trade without fear.” In a country where traders have come to expect nothing from leaders, this feels almost miraculous.

Then there’s Joseph Iroghama, a fabrics dealer who no longer watches his back every second. Armed extortionists once masqueraded as union enforcers, bleeding traders dry in broad daylight. That regime has ended. “This man didn’t talk — he acted,” Joseph declares. His sales have doubled. His confidence has returned.

The shift, it seems, is not just structural, it’s deeply psychological.

For Grace Aigbeka, a curator of culture and tradition, the contrast couldn’t be starker. “Obaseki made speeches. Okpebholo makes moves,” she says with quiet pride, pointing to newly painted walls and re-erected stalls. “He brought hope to the section that burned. He restored our dignity.” There’s no ambiguity in her voice. This isn’t partisanship, it’s gratitude with teeth.

Even Felix Ubokhedion, a measured trader in food items, testifies to what he calls a “psychological reboot.” He credits the governor’s interest-free loan announcement for boosting morale. “Even if we’re still waiting for disbursement, at least someone in power is thinking of us.”

That sense of inclusion – of being part of the plan, is perhaps Okpebholo’s most powerful currency. Because under the previous administration, traders felt like collateral damage in a bigger political game. Now, as Mary Efe puts it, “I go home with my profit without paying bribes. Before, it was union leaders dictating everything. Now, we are free.”

And it’s not just about economic freedom. There’s a cleaner environment now, literally. Waste management is back in government hands. Rodent infestations are down. Sanitation routines are regular. The fire-ravaged section of the market, which symbolized years of broken promises, is finally being rebuilt, with modern layouts and fire prevention systems in place.

This is not renovation. It’s resurrection.

Even more revolutionary is the grievance resolution desk: a direct interface between the traders and the government. “We now know who to talk to when there’s a problem,” Joseph notes. In a place where bureaucracy once meant abandonment, accessibility has become a breath of fresh air.

But perhaps what sets this moment apart is something intangible yet essential: “presence”. Not photo-op presence, but real, felt presence. “He is on the ground. He walks among us,” says Grace. “He listens, not with a mic, but with his eyes.”

This is not to say the previous administration lacked vision. Even some traders acknowledge that Obaseki had plans. But the plans felt distant. “He built theories. Okpebholo builds with his hands,” says Felix. The difference is not in intellect, it’s in execution.

Now, flood-prone alleys are navigable. Power lines are back. The banners may still be dusty, but the spirits are high. Oba Market is no longer just enduring, it is thriving.

In the end, Monday Okpebholo’s greatest achievement may not lie in a policy paper or campaign speech. It may be this: that in the clamor of Nigeria’s political theatre, he has turned his ears toward the marketplace, and found his leadership validated not by politicians, but by the people who live and breathe commerce.

It is in their voices that his name is being etched – not just in memory, but in the rhythm of their daily hustle. And in a country weary of forgotten promises, that, in itself, is revolutionary.